This post marks the end of my 27th year writing these updates on tropical Atlantic activity. During that time, I have written approximately 1380 posts spanning 460 tropical cyclones, 205 hurricanes, 94 major hurricanes, and 51 retired storm names. I know some of you reading this have been following along the entire time, but whether you've been reading these posts for 27 days or 27 years, I truly appreciate your continued interest!

The 2022 Atlantic Hurricane Season ends on Wednesday the 30th, and although it was much less active than initially expected, it definitely left its mark.

|

| Track map of all sixteen tropical cyclones that formed during the season. The storm's peak intensity and lowest central pressure are listed next to the names. |

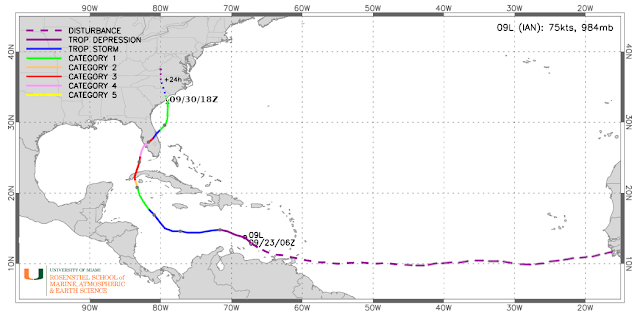

The season included 14 named storms, 8 of which became hurricanes, and 2 of those became major hurricanes. Climatologically, those numbers are 14, 7, and 3. But of course there's more to a hurricane season than the number of storms.

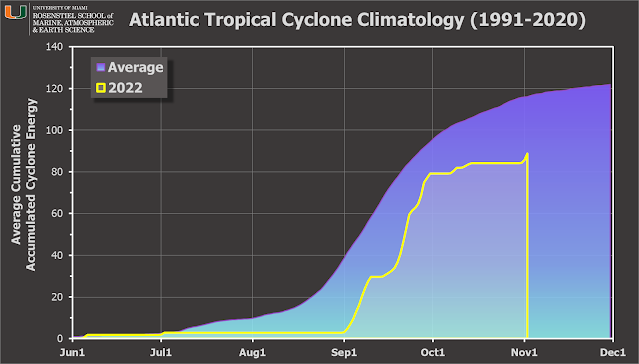

A commonly-used metric is the Accumulated Cyclone Energy, or ACE, and that is better at describing the overall duration and intensity of storms rather than the number of storms. This season ended up with just 80% of an average season's ACE... the lowest since 2015.

The distribution of activity was very unusual. July and August were dead (with the exception of Colin which was around for a few hours on July 2 over land), while November ended up as the second-most-active month of the season. On average, 22% of the season's ACE is accrued during August; this year it was 0%. And 47% of the season's ACE historically occurs during September; this year it was 80%.

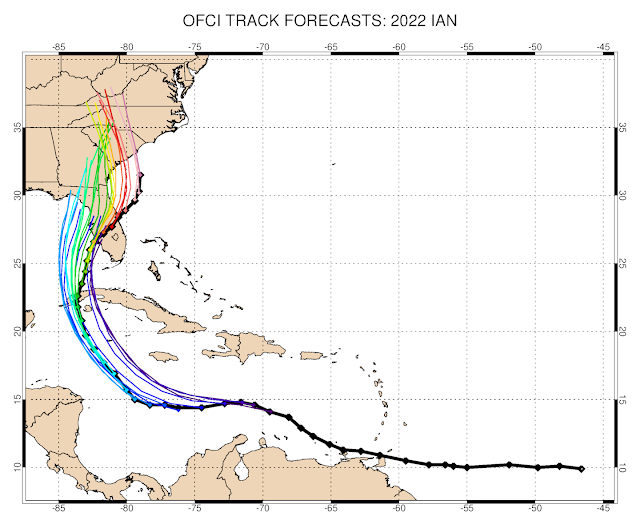

Of the fourteen named storms, four of them accounted for 74% of the total ACE and the other ten made up the remaining 26%. The top four were Fiona (28%), Ian (18%), Earl (15%), and Danielle (13%).

This November was only the fourth on record to feature three hurricanes, the others were 2001, 1887, and 1870. But two of the three were active simultaneously and the only other times that happened were 2001 and 1932.

On the flip side, this was only the fifth time since records began in 1851 that August went by with no activity; the last time was 1997. But 1997 was during a strong El Niño -- this was the first August with no tropical cyclone activity during La Niña on record. Truly a bizarre season.

All other things being equal, La Niña acts to enhance Atlantic tropical cyclone activity... and La Niña has effectively been in place since the middle of 2020. So what caused August to be so inactive even when it had that favorable background state? There were three factors that all played a role, though their origins are not yet clear to me. The mid-levels of the tropical and subtropical atmosphere were extremely dry, there was enhanced vertical wind shear over the tropical Atlantic, and the sea surface temperatures were anomalously cool over the tropical Atlantic. They combined to overwhelm and suppress anything that tried to form. Conditions quickly returned to normal once September began and then Danielle, Earl, Fiona, Gaston, Hermine, and Ian all formed during September.

For the first time since 2014, the first named storm formed after June 1, the official beginning of the Atlantic hurricane season. Even so, it formed a couple weeks earlier than average. The chart below shows the date of first named storm formation over the past fifty years in blue... the cyan line is the beginning of hurricane season (June 1), the magenta line is the median formation date (June 19), and the dashed gray line is the linear trend through the dates. There's a lot of interannual variability, but for a variety of reasons, this trend is decidedly getting earlier.

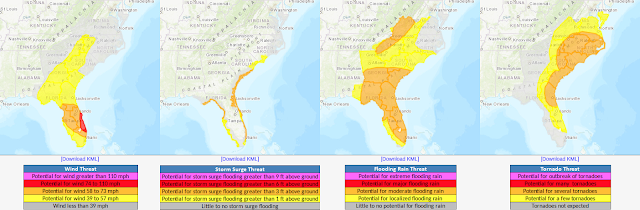

The most intense storm of the season as measured by peak wind speed was Ian, but Fiona had the lowest central pressure, the highest ACE, and the longest duration as a named storm. Ian also tops the list as the season's most deadly and most destructive. In a few months, the World Meteorological Organization's tropical cyclone committee will convene and debate which names should be retired from this list. Factors generally include how deadly and how destructive a storm was. Using preliminary numbers, the top five deadliest storms this season were Ian, Julia, Hermine, Fiona, and Nicole... the top five costliest storms were Ian, Fiona, Nicole, Julia, and Hermine. The same five storms made both lists but are just ranked differently.

Six countries experienced a hurricane landfall this season: Nicaragua (Julia), Belize (Lisa), Cuba (Ian), Dominican Republic (Fiona), United States (Ian and Nicole), and Canada (Fiona). Fiona was technically not a hurricane when it reached Nova Scotia, but was a Category-2-equivalent extratropical cyclone. Fiona also didn't technically make landfall in Puerto Rico, but passed close enough to deliver a crippling deluge of rain that was extremely destructive and killed over two dozen people. Although the the final counts are not yet known everywhere, there were approximately 350 people killed by tropical cyclones across the Atlantic during the 2022 season.

Finally, here is a preliminary look at how the National Hurricane Center's forecasts of track and intensity matched up against their own average errors over the previous five seasons. The track forecasts were very good this season, beating their average error at every forecast lead time. Out at five days (120 hours), the storm that made the greatest contribution to the errors was Gaston.

Moving to intensity, the forecasts were better than average out to three days (72 hours), then slightly worse at four days (96 hours) and noticeably worse at five days (120 hours). Those 4-and-5-day errors were dominated by Fiona.

There are several radar animations of the storms near land from this past season, from Alex to Nicole... all are available at https://bmcnoldy.rsmas.miami.edu/tropics/radar/

The 2023 hurricane season is six months away, and the list of names begins with Arlene, Bret, and Cindy... the list that was first used in 1981 and every six years since then. However, quite a chunk of the list has been retired and replaced:

1981: no names retired

1987: no names retired

1993: no names retired

1999: Floyd, Lenny

2005: Dennis, Katrina, Rita, Stan, Wilma

2011: Irene

2017: Harvey, Irma, Maria, Nate

2023: TBD

- Visit the Tropical Atlantic Headquarters.

- Subscribe to get these updates emailed to you.

- Follow me on Twitter

.gif)

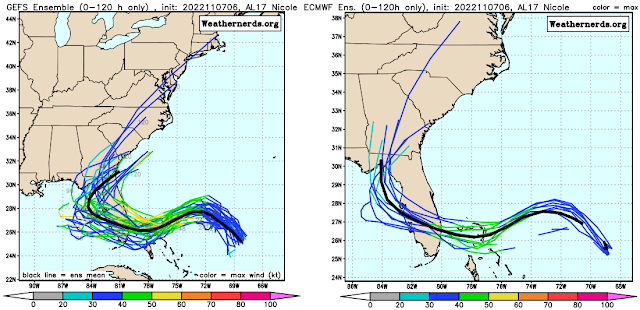

As eluded to in yesterday's post, both Lisa and Martin did indeed become hurricanes on Wednesday, and they're both active at the same time. This would not be too noteworthy in the core months of August, September, or October, but it's absolutely exceptional in November. In fact, it's only been observed twice before: in 2001 and 1932.

As eluded to in yesterday's post, both Lisa and Martin did indeed become hurricanes on Wednesday, and they're both active at the same time. This would not be too noteworthy in the core months of August, September, or October, but it's absolutely exceptional in November. In fact, it's only been observed twice before: in 2001 and 1932.

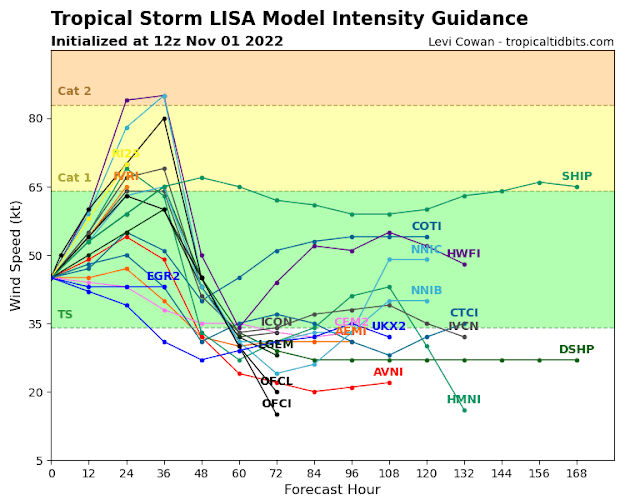

Tropical Storm Lisa formed today in the central Caribbean, just south of Jamaica. This has been a feature of interest for about six days already, but it failed to develop near the Lesser Antilles and the eastern Caribbean. Even today, it looks marginal on satellite, but aircraft data confirmed the organization and intensity necessary to upgrade it to a tropical storm.

Tropical Storm Lisa formed today in the central Caribbean, just south of Jamaica. This has been a feature of interest for about six days already, but it failed to develop near the Lesser Antilles and the eastern Caribbean. Even today, it looks marginal on satellite, but aircraft data confirmed the organization and intensity necessary to upgrade it to a tropical storm.

.gif)