Anyone who lives on a hurricane-prone coast or even watches television is familiar with the infamous "

cone of uncertainty" produced by the

National Hurricane Center. It begins as a point at the current position of a tropical cyclone and expands to show the potential position in five days. It is called the "cone of uncertainty" because the further out in time you go, the more uncertain the forecast becomes... and it tends to look like a cone!

|

| A "cone of uncertainty" for Hurricane Irma (left) and Hurricane Harvey (right). Both cones are from 2017 and are therefore identical to each other in their construction. |

The size of the cone is fixed for every storm during the entire hurricane season, but the size slowly evolves from year to year. If the storm is moving quickly, the cone will appear more elongated and if the storm is moving slowly, the cone will appear more compact... but it's the exact same cone. The examples shown above are from Irma (left) and Harvey (right); both storms were in 2017, so both cones are identical in their construction.

The cone is updated each year prior to the start of hurricane season, and it almost always shrinks each year too. Hurricane track forecasts are

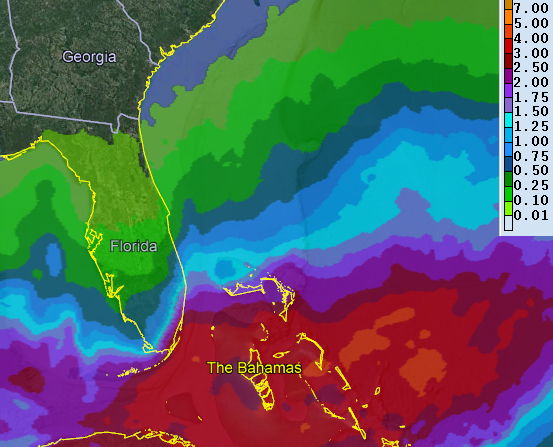

gradually improving, meaning that in general, there is less uncertainty where a storm will track now than there was a decade ago. In fact, a two-day forecast now is as accurate as a one-day forecast was a decade ago, and a five-day forecast now is more accurate than a three-day forecast was two decades ago! The map below shows a sample satellite image with the new 2020 cone overlaid on the 2015, 2010, and 2005 cones for comparison. Improvements are getting increasingly challenging to achieve because there can never be a perfect forecast of a chaotic system like the atmosphere.

So just how is the size updated each year? The National Hurricane Center uses its own track forecast errors over the previous five years to calculate a circle at each "lead time" (1 day, 2 days, ... 5 days). The size of that circle is designed to enclose the position of the storm's center with

2/3 probability, meaning that there's historically a 1/3 chance the storm will track outside the circle at that time. Lines connecting the various circles complete the shape of the cone. [Note that the 2020 cone size is thus determined from all track errors during the 2015-2019 seasons.]

Since the cone is so widely used yet sometimes misunderstood, here are some key refreshers:

- The cone does not tell you anything about where impacts will be experienced. Even for a perfect down-the-middle track forecast, impacts such as strong wind, heavy rain, storm surge, and tornadoes will extend beyond the cone.

- The cone does not tell you anything about the size of the storm. Regardless of how strong they are, hurricanes come in a wide range of sizes. Recently, NHC has added the observed size of the wind field to their cone graphics to help illustrate this (see the Irma and Harvey examples above... the orange and red shading indicates the extent of tropical storm and hurricane force winds at the time the forecast was issued).

- The cone does not tell you anything about the actual uncertainty associated with the forecast. Since the size of the cone is fixed, it cannot become more narrow or broad to accommodate a more or less predictable environment.

- Nothing magically happens at the edge of the cone. If a hurricane is approaching and you are scrutinizing each new forecast to see if you are inside the cone or not, you are missing the point of it. It is arbitrarily chosen to be the 67% historical probability threshold... a 75% probability cone would be larger, and a 50% probability cone would be smaller.

- If you use the cone graphics from NHC, there is some information about intensity provided. At each forecast point, there is a letter written inside the black dot corresponding to a general intensity range: D (tropical depression), S (tropical storm), H (hurricane), and M (major hurricane (Category 3+)). But keep in mind that there is uncertainty associated with the intensity forecasts too!

To think about a cone of uncertainty for

intensity, consider this: averaged over the past five years (2015-2019), the mean error in a 1-day forecast is +/- 9 mph, the error in a 3-day forecast is +/- 15 mph, and the error in a 5-day forecast is +/- 20 mph. But there is also a wide range of values that go into those averages, meaning that there is a small probability of a very large error and a small probability of near-zero error.

Other important terms:

Storm Surge Watch: the

possibility of life-threatening inundation from rising water moving inland from the shoreline generally

within 48 hours.

Storm Surge Warning: the

danger of life-threatening inundation from rising water moving inland from the shoreline generally

within 36 hours.

Hurricane Watch: sustained winds of 74 mph (64 knots or 119 km/hr) or higher are

possible. Because hurricane preparedness activities become difficult once winds reach tropical storm force, the hurricane watch is issued

48 hours in advance of the anticipated onset of tropical-storm-force winds.

Hurricane Warning: sustained winds of 74 mph (64 knots or 119 km/hr) or higher are

expected. Because hurricane preparedness activities become difficult once winds reach tropical storm force, the warning is issued

36 hours in advance of the anticipated onset of tropical-storm-force winds.

Tropical Storm Watch: sustained winds of 39-73 mph (34-63 knots or 63-118 km/hr) are

possible within the specified area

within 48 hours.

Tropical Storm Warning: sustained winds of 39-73 mph (34-63 knots or 63-118 km/hr) are

expected somewhere within the specified area

within 36 hours.

Strong winds and thunderstorms arrive well before the center of the storm (sometimes a couple days), so when the time comes, be sure to plan and finalize your preparations prior to the expected arrival of tropical storm force winds, not the expected arrival of the center.

And if you missed it earlier, I have some general hurricane information and preparedness tips at

http://bmcnoldy.blogspot.com/2019/04/2019-hurricane-season-intro-local.html

Anyone who lives on a hurricane-prone coast or even watches television is familiar with the infamous "cone of uncertainty" produced by the

Anyone who lives on a hurricane-prone coast or even watches television is familiar with the infamous "cone of uncertainty" produced by the